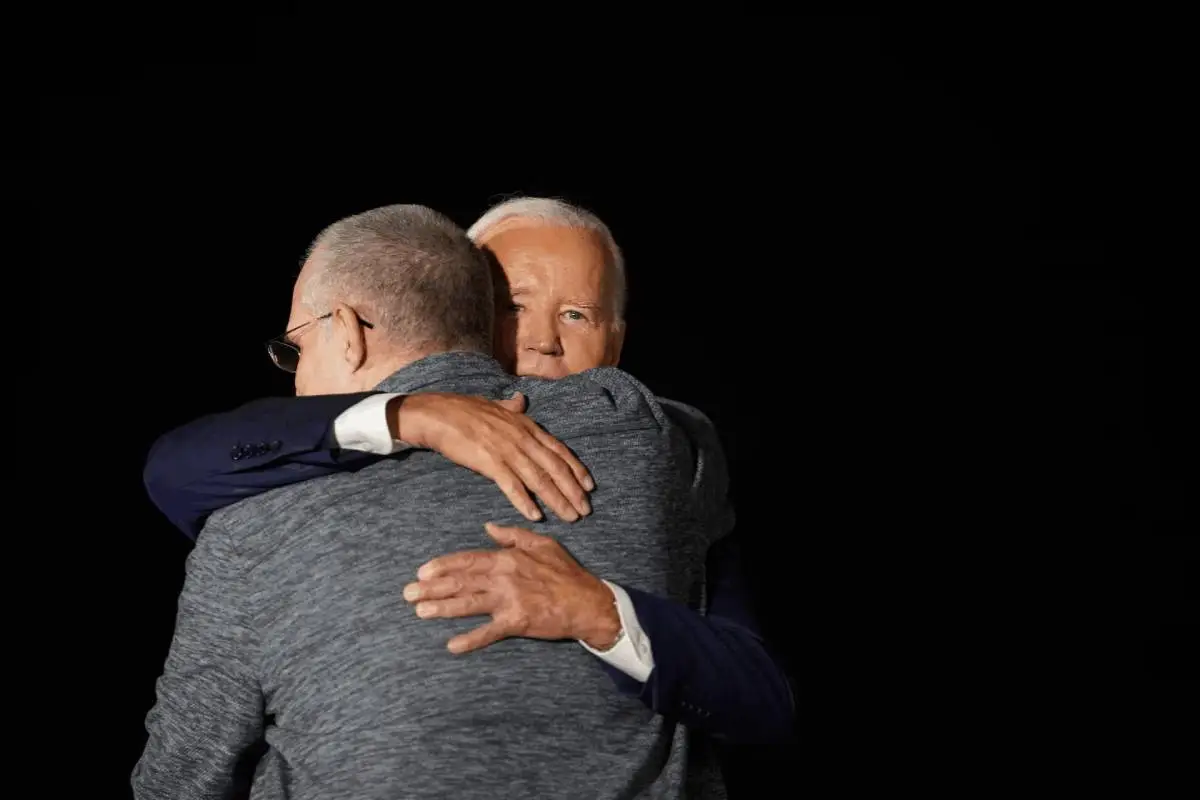

Prisoner Swap A Legacy Boost For Biden

Photo: Reuters/Nathan Howard

By Matt Spetalnick and Andrea Shalal

WASHINGTON, DC (REUTERS) – The largest prisoner exchange between Russia and the West in decades could help U.S. President Joe Biden burnish his foreign policy legacy in his waning months in office and boost Vice President Kamala Harris in her bid for the White House.

But, from the perspective of Washington, it came at a significant cost: the freeing of Russians convicted of serious crimes in exchange for Americans the U.S. deems unjustly detained, a trade-off some experts say might encourage hostage-taking by US foes.

Though Biden’s record on the world stage is likely to be heavily defined by the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, the complicated, multi-country prisoner swap with Moscow on August 1 provided a much-needed foreign policy accomplishment amid heightened global tensions.

It was all the more difficult to reach a landmark deal against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, in which the US is arming Kyiv against a Russian invasion, sending relations between Moscow and Washington to the lowest point since the Cold War.

The prisoner swap goes a long way, however, toward addressing what Biden’s aides have long identified as a key priority on his foreign policy agenda, especially after he ended his reelection bid and endorsed Harris for the Democratic nomination.

“It is an achievement. Smart diplomacy produced it,” said Dennis Ross, a former Middle East adviser in Republican and Democratic administrations. “Getting back Americans seized and held unjustly is part of the responsibility any government has.”

Biden hailed the prisoner swap, including the release of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and ex-Marine Paul Whelan, as a “feat of diplomacy,” and by extension, it could give Harris a positive note to sound on the campaign trail against Republican nominee Donald Trump.

But experts say Biden will have to fend off Republican criticism of the deal and, in a broader sense, will still have plenty of work to do to polish his foreign policy record for the history books.

The prisoner swap finally came together after more than a year of painstaking negotiations. It also involves Germany and other European allies, with 24 prisoners changing hands, including the return of four to the U.S. and eight being sent to Russia.

Crucial to the deal was Germany agreeing to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s main demand for the release of Vadim Krasikov, who was convicted for the murder of a former Chechen militant.

Jeff Rathke, a former U.S. diplomat and president of the American-German Institute at the Johns Hopkins University, said the exchange reflected much-improved relations between Germany and the United States under Biden compared to Trump.

The German government consented, he said, “because the United States and Germany had a level of confidence, trust and mutual interest that allowed something difficult in the German justice system to occur and could cause criticism at home.”

However, there is no sign that Putin is looking to repair ties with Washington, and Biden administration officials said the deal appeared to be a one-time exchange.

It was unclear why Putin decided to work out a big prisoner swap with Biden instead of holding off for the possibility that Trump – who has shown himself more amenable to Moscow’s interests – might be back in the White House in January.

But Putin may have calculated that it was better to do business with Biden instead of waiting for the next administration and possibly having to start from scratch.

U.S. officials believe it was a one-off deal because of Germany’s willingness to participate and there was no guarantee such an offer would still be on the table under the next president.

Trump had repeatedly insisted that, if elected, he could easily get Gershkovich released, writing in May that Putin “will do that for me, but not for anyone else, and WE WILL BE PAYING NOTHING!”

Dozens of U.S. nationals are still what Washington terms “wrongfully detained” or held hostage by foreign governments, including some in Russia and others in China and Iran, or with non-state actors such as the Palestinian militant group Hamas.

While Biden promised to continue seeking their release until he leaves office on Jan. 20, it is likely the task will be inherited by the next president.