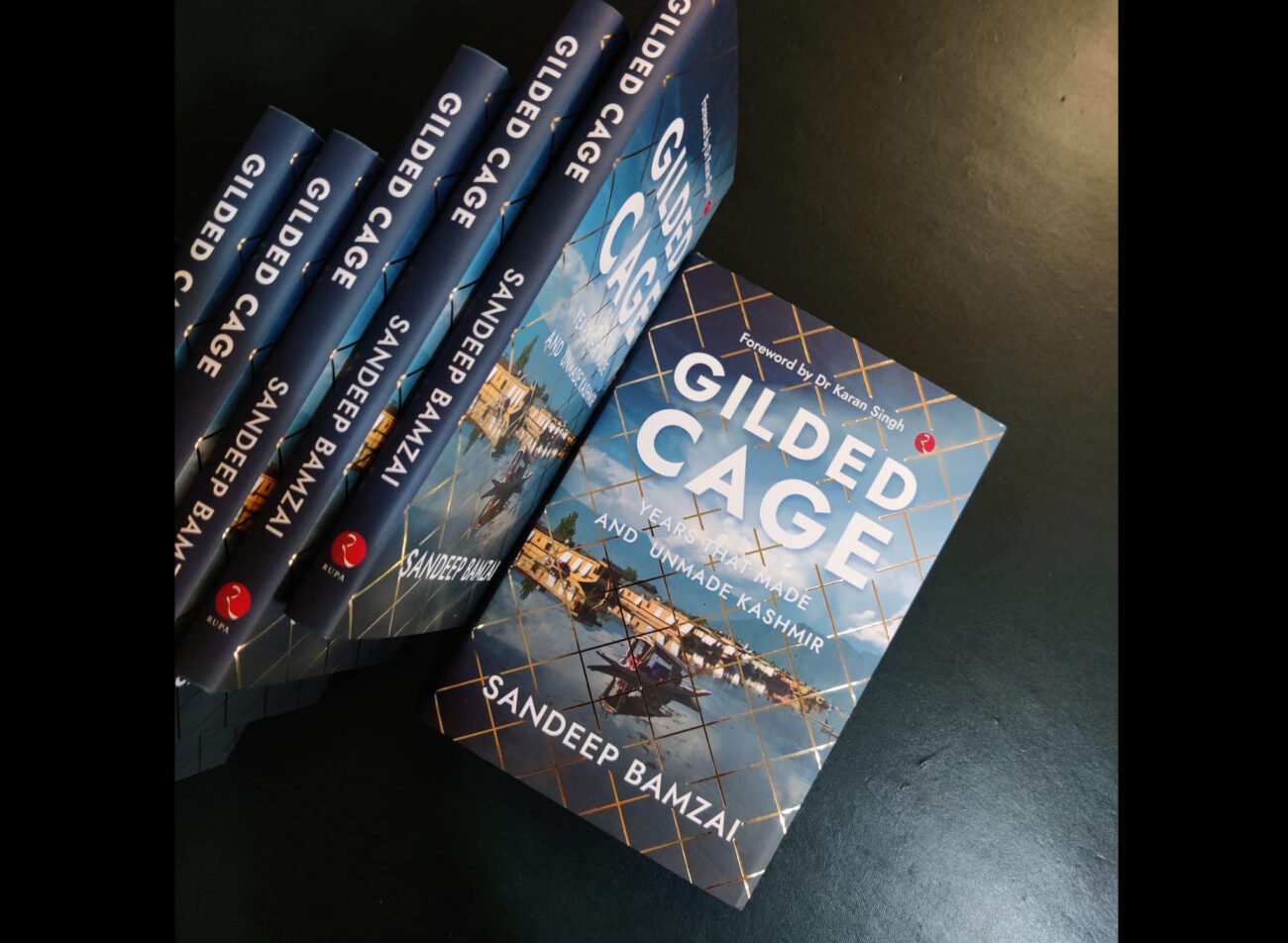

Sandeep Bamzai’s Journey Through The Gilded Cage Of History

BENGALURU, (IANS) – In Sandeep Bamzai’s latest addition to the Kashmir trilogy, “Gilded Cage: Years That Made and Unmade Kashmir” (Rupa), the author navigates the intricate political landscape that defined Kashmir’s accession to India. In this book, Bamzai introduces readers to four significant characters, offering a nuanced perspective that extends beyond the well-explored narratives of Sheikh Abdullah and Hari Singh.

In a pivotal moment in the aftermath of India’s independence in 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, chose to accede his state to the Dominion of India by executing an Instrument of Accession under the provisions of the Indian Independence Act 1947. This significant decision was accepted by the then Governor-General of India, Lord Mountbatten, on October 27, 1947.

In a letter addressed to Maharaja Hari Singh on the same day, Lord Mountbatten expressed the Indian government’s intention to settle the question of the state’s accession through a reference to the people, once law and order had been restored in Jammu and Kashmir, and the invaders expelled. This commitment reflected a democratic approach to determining the region’s political destiny.

However, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, vehemently opposed the accession, labelling it as “fraudulent”. Jinnah contended that Maharaja Hari Singh had betrayed trust by acceding to India, particularly at a time when a standstill agreement, initiated at the Maharaja’s personal request, was still in effect. This disagreement over the legitimacy of the accession laid the groundwork for enduring tensions between India and Pakistan over the Kashmir issue.

The annual celebration of Accession Day on October 26 commemorates this historic event.

Bamzai’s book explains the intricacies of this critical juncture in history, providing readers with a comprehensive understanding of the facts surrounding the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India. Through meticulous research and insightful analysis, Bamzai offers valuable insights into the complexities and controversies that shaped the destiny of this region.

The book begins by unravelling the complex political ideologies of key figures such as Maharani Tara Devi, Ram Lal Batra, Ram Chandra Kak, and Swami Sant Deo. Each character’s stance on Kashmir’s future ranging from independence to accession with India or Pakistan sets the stage for the tumultuous events that follow. Bamzai masterfully captures the historical moment when Lord Mountbatten attempted to sway Maharaja Hari Singh away from declaring independence, an endeavor that ultimately proved unsuccessful.

The heart of Bamzai’s narrative lies in the third part of his Kashmir trilogy, which beautifully documents the contentious years leading to the “making and unmaking” of the Kashmir issue. Drawing from previously inaccessible private papers, the author sheds light on the intrigues and complexities that marked the period between the sunset years of the British Raj and the arrest of Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah on August 8, 1953.

The book compellingly explores the dynamics between key players, from Jinnah’s fervent desire for Kashmir to Sheikh Abdullah’s vehement opposition. Jawaharlal Nehru’s strategic view of Kashmir as a showcase for his brand of secular politics, Maharaja Hari Singh’s pursuit of independence, and the subsequent disillusionment of Kashmiri masses are vividly portrayed. Bamzai’s use of unpublished papers, particularly those of his grandfather K.N. Bamzai, adds a layer of authenticity to the narrative.

During the narrative, the author does not shy away from addressing the sensitive issue of the migration of Kashmiri Pandits, providing a sobering account of this significant chapter in Kashmir’s history. However, the omission of details regarding the killings of National Conference workers during the period of turmoil leaves a noticeable gap in the comprehensive coverage of events.

Bamzai’s writing style is both lively and insightful, making the book an engaging read. The incorporation of new details, particularly from Dwarkanath Kachru’s letters to Nehru, offers fresh perspectives on Sheikh Abdullah’s mindset in the 1950s. However, the book could have been enriched by dedicating more pages to the roles played by Prime Minister Ram Chandra Kak and his advisor Swami Sant Deo.

Despite these minor shortcomings, “Gilded Cage.” stands as a valuable contribution to the political literature surrounding Kashmir in 1947. The author’s deep dive into hitherto unpublished papers, coupled with personal insights from his grandfather’s tenure as Sheikh Abdullah’s Private Secretary and OSD to Nehru, adds a unique dimension to the narrative.

As with any historical account, there are moments where the narrative could benefit from a more comprehensive examination of certain events. The book, however, successfully captures the essence of Kashmir’s political upheavals during a critical period in its history.

“Gilded Cage.” is a quick yet fascinating read that provides a fresh perspective on Kashmir’s complex political history. Sandeep Bamzai’s meticulous research and compelling storytelling make this book an invaluable resource for scholars, journalists, and readers seeking a deeper understanding of the forces that shaped and reshaped the destiny of Kashmir.