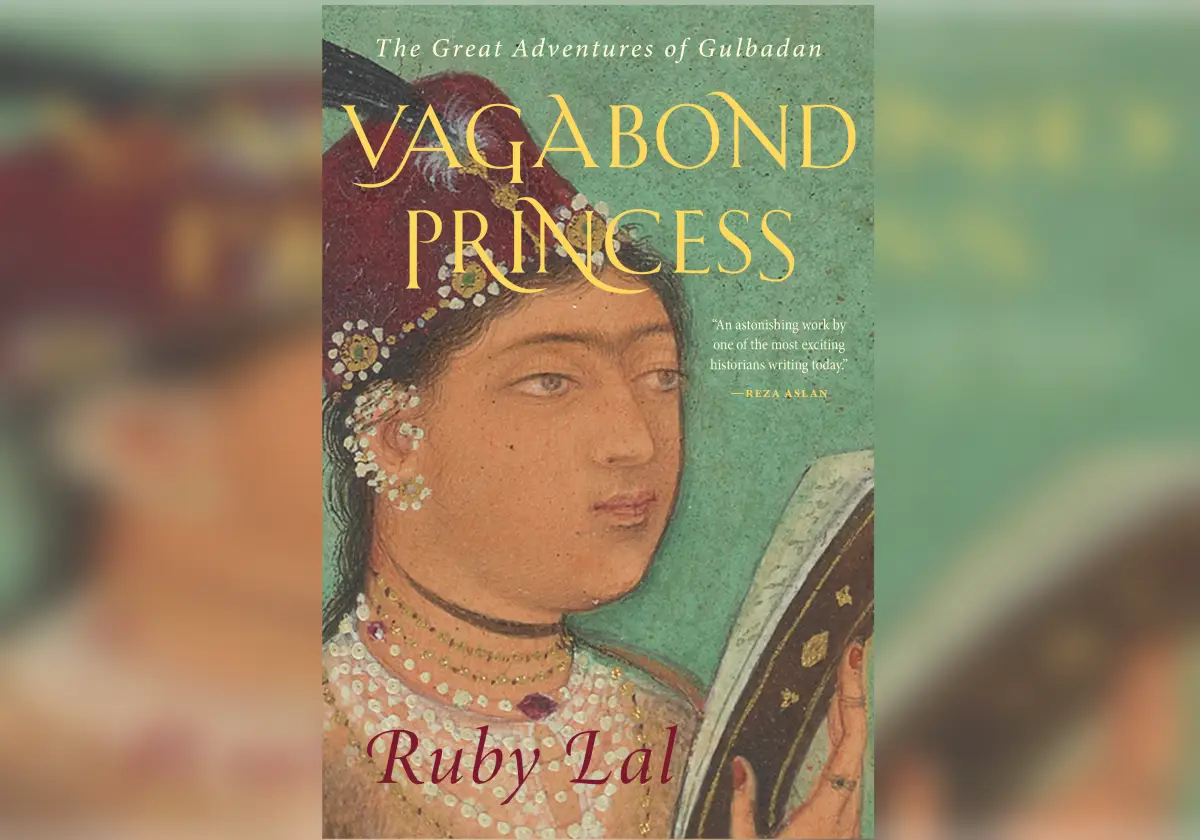

Princess Gulbadan – A Woman’s View Of the Mughal World

India-West Staff Reporter

From the sprawling, storied Mughal Empire there is a single surviving work of prose written by a woman: the memoir of the brave and brilliant Princess Gulbadan. A participant in the innermost circles of the Empire, Gulbadan (1523–1603) chronicled the events of her dynasty and her lifetime from an authoritative and thoroughly feminine perspective—like a Mughal Jane Austen. Her book, in fact, may be the only remaining work of prose by a woman from this time.

In Vagabond Princess: The Great Adventures of Gulbadan which releases February 27, acclaimed historian Ruby Lal becomes the first scholar to analyze Gulbadan’s long-overlooked memoir.

Lal, a professor of South Asian History at Emory University and the author of ‘Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan,’ which was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in 2018, deftly examines Gulbadan’s words and draws from a multitude of contemporary textual, artistic, and architectural sources to illuminate the Princess’s lush and multicultural world.

Daughter of the first Mughal Emperor, sister to the second, and aunt to the third, Gulbadan, the book begins in Kabul and follows the peripatetic royal household through decades of travels and political pursuits. The Mughals had often moved across long distances, living for extended periods in the open country in royal tents pitched in gardens, and in citadels. Gulbadan longed for the exuberant itinerant lifestyle she’d long known.

With Akbar’s blessing, Gulbadan led a remarkable and unprecedented four-year pilgrimage of Mughal women to the distant Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina and beyond. Amid increasing political tensions, the women were expelled for their “un-Islamic” behavior, a thinly veiled effort to curb Mughal influence in the Holy Cities, controlled at the time by the Ottoman sultans of Turkey. Their travels home included a dramatic shipwreck in the Gulf of Aden.

After her return to India, Akbar asked Gulbadan to record her memories of the Mughal Dynasty to serve as a source for the first official history of the Empire. What she wrote was unparalleled in both form and content. She captured the gritty and fabulous daily lives of ambitious men, subversive women, brilliant eunuchs, devoted nurses, gentle and perceptive guards, captive women, and children who died in war zones.

But there is a literary mystery at hand. Housed today in the British Library, the lone surviving copy of Gulbadan’s memoir abruptly cuts off mid-sentence in folio 83. Where are the remaining pages? Why is there just one copy of this book when it was the Mughal tradition to create several copies of all important works? Was someone seeking to silence this woman and her view?

Lal breathes gorgeous life into a figure and her time and place in a history that has long been dominated by men’s actions and words. Her book is a feminist history that shape-shifts our views of the magnificent Mughals as we begin to see and feel Gulbadan’s world.