Crisis Of Continuity: Hindu America Needs Institutions Of Learning Not Just Temples

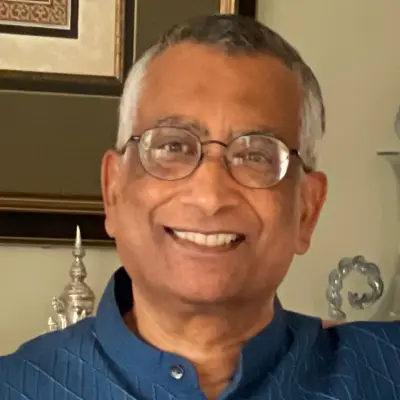

By Dr. Jai G. Bansal

On a typical weekend in many American cities, the Hindu presence is easy to see. Newly built temples rise in suburban landscapes. Diwali celebrations fill convention centers and public squares. Yoga studios, Sanskrit terms, and Hindu symbols circulate comfortably in mainstream culture. By outward measures, Hindu identity in the United States appears visible, confident, and socially secure.

Yet this visibility obscures a structural shift that should give us serious pause.

Across many Hindu households, intergenerational transmission is thinning. Children often grow up knowing that they are Hindu, but with limited understanding of what that identity entails as a way of life. Temple attendance is common, but explanatory depth is not. Festivals are celebrated but rarely shape the rhythm of the year. Rituals are performed, yet their meanings remain opaque. Identity is present but lightly held.

This pattern does not arise from rejection or conflict. It emerges through absence. Research on immigrant religious retention consistently shows sharp weakening by the second and third generations where education and transmission are informal and optional. Hindu Americans are not an exception. As first-generation immigrants age, the informal modes of inheritance they relied on—habit, language, unspoken assumptions—lose their effectiveness. What once moved naturally within the household no longer finds a stable pathway.

Many young adults continue to identify as Hindu in a cultural or ancestral sense, but struggle to articulate beliefs, practices, or ethical frameworks in their own terms. This is not always experienced as loss. Professional success, social integration, and public affirmation create little immediate pressure to notice what is thinning. Prosperity can obscure erosion, allowing continuity to appear intact long after its foundations have weakened.

The challenge, then, is not external hostility or social exclusion. It is continuity under minority conditions. When a tradition is visible without being formative, celebrated without being taught, and affirmed without being structured, erosion proceeds quietly, often unnoticed.

Ambient Dharma Meets Minority Reality

The weakening of transmission did not begin with indifference or a conscious rejection of tradition. It emerged from the interaction of inherited habits and new conditions. Hindu families who migrated to the US were disproportionately drawn from educated, urban, and professionally mobile backgrounds. Academic credentials and economic stability enabled rapid integration, but they also reduced reliance on collective institutions that had once carried civilizational continuity.

Many parents brought with them an upbringing shaped in urban India after the 1960s, where dharma functioned less as something explicitly taught and more as an ambient presence. Religious meaning was absorbed through participation rather than instruction. The calendar followed Hindu rhythms. Festivals, fasting days, and life-cycle rituals structured the year. Language, food habits, and social customs carried familiar references. Children learned by living inside a civilizational environment that quietly reinforced belief and practice.

In that context, formal teaching was often unnecessary. Even when rituals were not explained in detail or texts studied systematically, the surrounding society filled the gaps. Public life echoed religious vocabulary. Social expectations reinforced shared norms. Dharma appeared self-sustaining.

In the US, however, this model is often reproduced without adjustment, despite fundamentally different conditions. The broader environment offers little reinforcement. Schools, peers, media, and public institutions reflect a different civilizational framework. Yet household practices frequently remain informal and episodic. Prayer is irregular. Engagement with texts is limited. Civilizational history is discussed, if at all, in fragments. Hindu culture surfaces mainly during festivals or family ceremonies rather than shaping daily routines or moral reference points.

Economic success makes this drift easy to overlook. Children perform well academically, navigate social spaces with ease, and move confidently through American institutions. There is little immediate cost to cultural thinning. Continuity is assumed rather than cultivated.

Over time, familiarity replaces understanding. Children recognize symbols and participate in rituals, but struggle to explain meaning or significance. Dharma remains visible but peripheral. What once worked in a civilizational majority setting begins to falter quietly in a minority one.

Interfaith Homes and Western Education

As foundational grounding weakens, other forces tend to accelerate the drift. Two of the most significant are the structure of interfaith households and the nature of the American education system. Neither operates through hostility or exclusion. Both work through default settings in a society where minority traditions require deliberate effort to sustain themselves.

Interfaith marriage has become increasingly common among Hindu Americans, particularly among the US-born and highly educated. Most such marriages are entered with goodwill and a sincere desire to honor both backgrounds. Children are often raised with language that emphasizes balance and openness: both traditions matter, both belong to the family story, and identity choices can be made later.

Yet households require coherence to function. Daily routines, school calendars, moral language, and social reference points tend to follow a single framework. In the US, that framework remains shaped by Christian-derived norms, even when families describe themselves as secular. Without intentional structure, the minority tradition recedes, appearing mainly during festivals or moments of cultural display. This is rarely deliberate. It reflects how default environments operate.

Education reinforces this imbalance. At the K–12 level, Hindu civilization is often introduced through a narrow focus on caste, hierarchy, and social inequality, treated as defining features rather than historically contingent categories shaped by colonial interpretation. Philosophical diversity, ethical reasoning, and metaphysical inquiry receive limited attention, while Hindu contributions to mathematics, astronomy, linguistics, and logic are frequently absorbed into the Western canon without attribution.

At the university level, critique increasingly displaces comprehension. Hindu traditions are examined primarily through frameworks of power and identity politics. Terms such as “Hindutva” circulate as charged categories, often detached from civilizational context. Students with strong grounding can navigate these narratives critically. Those whose inheritance is already thin often cannot.

In such cases, external narratives fill the space left by weakened transmission. Distance replaces curiosity, and critique becomes a substitute for understanding. None of this requires hostility to be effective.

Where Institutions Fall Short

In principle, institutions exist to stabilize what households cannot sustain on their own. In practice, many Hindu institutions reflect and reinforce the same patterns that weaken transmission at home. Temples remain central to community life, but they are rarely structured as institutions of sustained formation. Programming emphasizes celebration and devotion over education. Festivals fill calendars and cultural events draw crowds, while structured curricula, trained educators, and long-term pedagogical planning remain limited. Children learn how to attend, but not how to understand or explain what they are doing.

This institutional thinness mirrors household-level ambiguity. In many families, a familiar framing prevails: all religions are essentially the same, differences need not be emphasized, and spirituality matters more than form. Offered in good faith, this language signals tolerance and avoids discomfort. Yet it leaves children unclear about what their own dharmic inheritance actually consists of. Institutions rarely correct this ambiguity. More often, they normalize it.

This outcome is not inevitable. The experience of the BAPS shows what changes when institutions take transmission seriously. In BAPS communities across the United States, temples function as integrated educational ecosystems. Children move through age-specific programs combining scriptural study, ritual practice, ethical discipline, and seva. Attendance is regular, expectations are clear, and learning is sequential. Youth are entrusted early with responsibility, including teaching younger students. Difference is explained calmly and confidently, without hostility and without dilution.

This seriousness does not isolate participants from wider society. BAPS youth are widely represented among accomplished professionals in medicine, engineering, science, law, and business. Continuity and modern achievement reinforce each other.

Elsewhere, philanthropy entrenches the opposite pattern. Hindu Americans have the resources to build durable educational institutions, yet significant giving flows toward elite Western universities and cultural organizations that signal social arrival. Hindu educational infrastructure remains fragmented and volunteer-dependent. This reflects not a lack of capacity, but a misalignment of priorities.

The Cost of Inaction

The consequences of doing nothing are no longer abstract. As the first generation of immigrants passes, lived memory and embodied knowledge disappear with them. Over one or two generations, Hindu identity may persist in name and visibility while hollowing out as a lived framework. Temples may remain active and festivals well attended, yet dharma no longer shapes everyday conduct or moral reasoning.

This erosion is cumulative and difficult to reverse. Once transmission weakens beyond a certain threshold, continuity cannot be restored through symbolism or occasional engagement. Communities that delay investment in formation lose the capacity to explain themselves, renew themselves, or prepare the next generation to engage the world with clarity. Identity survives, but coherence does not.

The priorities that follow are collective. Continuity under minority conditions requires treating dharmic education as foundational, building institutions designed for long-term formation, and aligning philanthropic resources with civilizational needs rather than external prestige. Goodwill and tolerance remain important, but they cannot substitute for structure.

What is at stake is not whether Hindu identity remains visible, but whether it remains lived – capable of shaping meaning, responsibility, and moral imagination rather than surviving only as memory or display.

(Bansal is Vice President of Education at the Vishwa Hindu Parishad of America and a member of its Governing Council and Executive Board. He has been a Chief Scientific Officer at a petrochemical firm and advisor to the US Department of Energy.)

Sam

/

Hindu America already has institutes of learning. here are some:

Stanford University

Columbia University

Harvard

It needs more temples because temples are overcrowded. Look around a neighborhood. It appears there is a church at every block.

January 22, 2026Sam

/

If Hindu Indians build schools like churches that prioritize Christians and require mandatory study of Hindu scriptures like in 7th Adventist schools, USA will be up in arms. Even the sick-ular Indians will jump in calling them madrasas.

January 22, 2026Natarajan Sivsubramanian

/

what are the remedies suggested

January 22, 2026Ananth Sethuraman

/

Students are used to learning conceptually. Let the concepts and practices associated with atma saksatkara (aka kaivalya, moksha, nirvana, self-realization) also be taught at a fairly young age. Let them learn that even exam tensions are happening in the vyavaharika domain.

January 24, 2026G.S.Satya

/

Pranams Bansal ji. I agree with your points of view here.

January 26, 2026May I suggest you visit the web site of our Shiva Vishnu Temple, Livermore and get acquainted with our activities.

The Motto of our temple since its beginning Is HOME FOR HINDU RELIGION, CULTURE THOUGHTS & SPIRIT which covers all your excellent points.

We conduct Educational Classes and we donate School Scholarships including the larger community. Our annual Grants in Aid program is highly popular and admired.

Our temple rituals, festivals and volunteer participations shape the personailty of the Youngsters and Adults.

We just had a Seniors Day and the annual Dance Festival “Arudra Natyanjali” all day events.

The children of our community excel academically, learning our classical music and dance. I can proudly say that some of them will win Nobel prizes for their career work and credit our temples and classical arts training for their achievement. We will have many C.V. Ramans, C.V. Chandrashekhars and Madame Curies in our next generations. And they will credit the influence of our temples and classical arts training for their achievements.

I feel blessed to be a volunteer from the beginning of our Shiva v Vishnu Temple.

Swamy Chidannda says “To Live More, GoTo Livermore” Om.