South Asia’s Acute Climate Vulnerability, Low Adaptability

By Farwa Aamer

The sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change highlights South Asia’s acute vulnerability to climate change, which is exacerbated by developmental constraints, pervasive poverty, governance challenges, and reliance on climate-sensitive livelihoods.

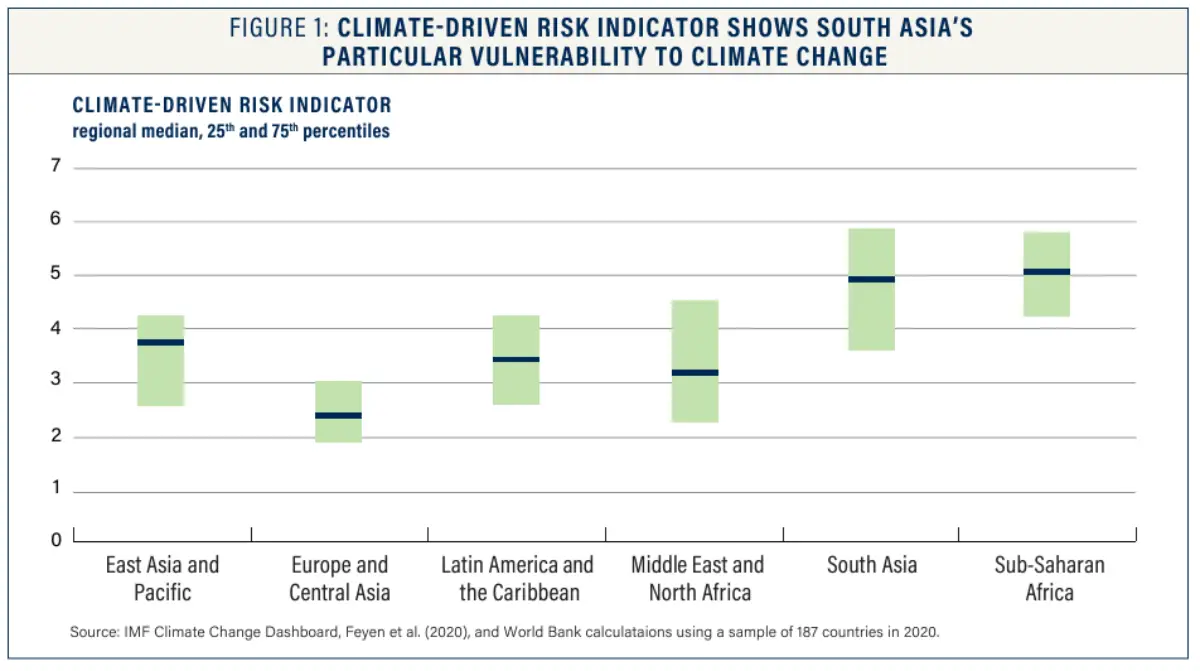

The International Monetary Fund’s Climate Change Dashboard shows that South Asia’s climate vulnerability index is among the highest in the world, with a much higher median than other subregions in Asia.

The University of Notre Dame’s Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) index demonstrates that countries like Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, and Nepal rank high on climate vulnerability but low on readiness to adapt, reflecting their limited capacity to cope with the impacts of climate change.

Although South Asia contributes only 8% of global carbon emissions, the region bears a disproportionate share of climate-induced adversities, underscoring the urgent need to build climate resilience.

Extreme weather phenomena in South Asia have escalated in both frequency and severity. The summer of 2024 witnessed severe heatwaves across the region, particularly in India and Pakistan, where temperatures soared above 50 degrees Celsius, with Delhi experiencing its hottest day on record. The region is experiencing a “new climate normal” as more than half of South Asia’s population, around 750 million people, have already been affected by one or more climate-related disasters in recent decades.

Erratic monsoon patterns are causing severe flooding and extended droughts, disrupting agriculture, which is crucial for food security and employs a significant portion of the population. The catastrophic floods in Pakistan in 2022, which impacted more than 33 million people and resulted in total damages over $14.9 billion, exemplify the devastating effects of these changes.

Rising sea levels further threaten coastal areas, exacerbating saltwater intrusion and displacing millions of people in the region. South Asia’s reliance on critical transboundary river basins — such as the Indus, Brahmaputra, and Ganges — compounds its water security challenges, as the region possesses only 4% of the world’s annual renewable water resources, leading to significant supply-demand imbalances.[8]

The socioeconomic repercussions of climate change disproportionately affect marginalized and disadvantaged communities, who have the least capacity to adapt and recover. Vulnerable groups, including women, children, and the elderly, face heightened risks to their health, livelihoods, and overall well-being.

UNICEF estimates that 76% of children under age 18 in South Asia are exposed to extremely high temperatures, highlighting the urgent need for robust climate resilience strategies. Adverse climate impacts further strain economies that are already burdened by crippling external debt. Countries such as Pakistan and Sri Lanka lack the fiscal capacity to manage the repercussions of climate change and meet their development needs at the same time.

Building climate resilience in South Asia is thus not merely an environmental necessity but a socioeconomic imperative, especially as the countries are ill-equipped to adapt to the climate crisis at the required pace.

(Published by the Asia Society Policy Institute in Collaboration with the World Bank South Asia Region.)