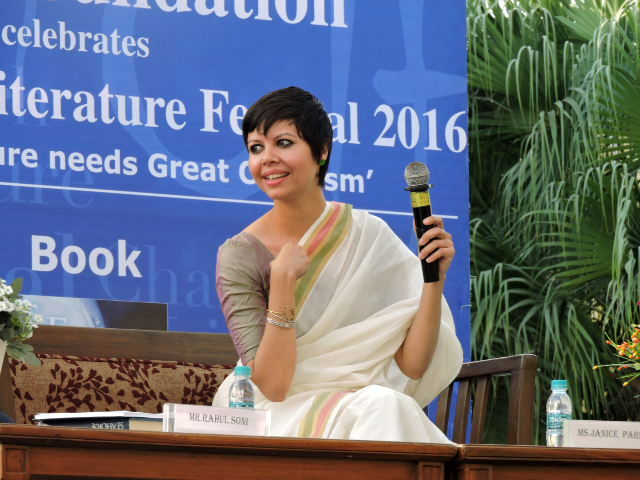

Local Stories At Risk Due To Nation Building: Janice Pariat

NEW DELHI, (IANS) – Lyrical, and with a certain delicacy, Janice Pariat’s latest ‘Everything the Light Touches’ carries multiple narratives, with diverse tales of four people, whose lives may not touch, but tales seldom lose connection with each other.

In contemporary times, Shai, a young woman, just out of work goes to her hometown Meghalaya (Delhi-based Pariat grew up between Shillong and several tea estates in Assam), and explores her roots. In British India, a woman botanist wants to prove herself in a system that favors men. In 1786, legendary German poet, novelist, and playwright Johann Wolfgang Goethe travels through Italy, realizing the shortfalls of the scientific processes while in 1732, botanist Carl Linnaeus journeys through the Lapland region in Finland.

Pariat says about the book, drawn richly from scientific and botanical ideas, “These are stories that come from places that were colonized and how we learn about the natural world… These are also tales that are not given enough importance even within a cultural context. Thus, these are the unequal stories that I kind of set out to equalize. The story of Linnaeus is connected to Shai and how they exist in a continuum,” she says.

“Linnaeus was the father of taxonomy, and Goethe is almost this national figure for Germany; here I was, this very non-white person from a little corner in the world wishing to place them on a page. Of course, I did ask myself many times — who am I to do this? How did I have the courage to? I had to really work to overcome that fear and hesitation. It felt like I was not capable and did not have the right to do that. At some point, I began reading other fiction that placed similar figures into this fictional world, that gave me courage.”

Talk to her about the fact that the effort to build a monolithic culture is an attempt to erase local stories, and she asserts that in the grand project of nation-building, the places she comes from have always been a risk.

“Our histories have been forgotten or passed on even within the people who live in those hills. We have little idea about our own wars. So yes, it is sad, but it has been happening for a long time — with both colonization and neo-colonization.”

Considering, Pariat is not a science student, was the research tough? She stresses that she was infinitely fond of botany, but the “ridiculous” education system made her choose between the arts and science.

“Hopefully it is changing now. I would have loved to study botany with literature. There are so many of these disciplines that can inform each other. Before writing this book, it was about beginning from scratch. I sat with a book on botany for months… I had to learn what it was, to begin with and how mainstream sciences were — it was like going back to college. It was only when I understood how botany was taught and what it was, then I managed to read and understand it,” says the author.

Pariat believes that it is important for writers to be disruptive for this is what they are here to do — to make everyone question things and make them a bit uncomfortable. “And that always takes some degree of discomfort. You cannot undergo a transition without some kind of pain, grief, or loss.”