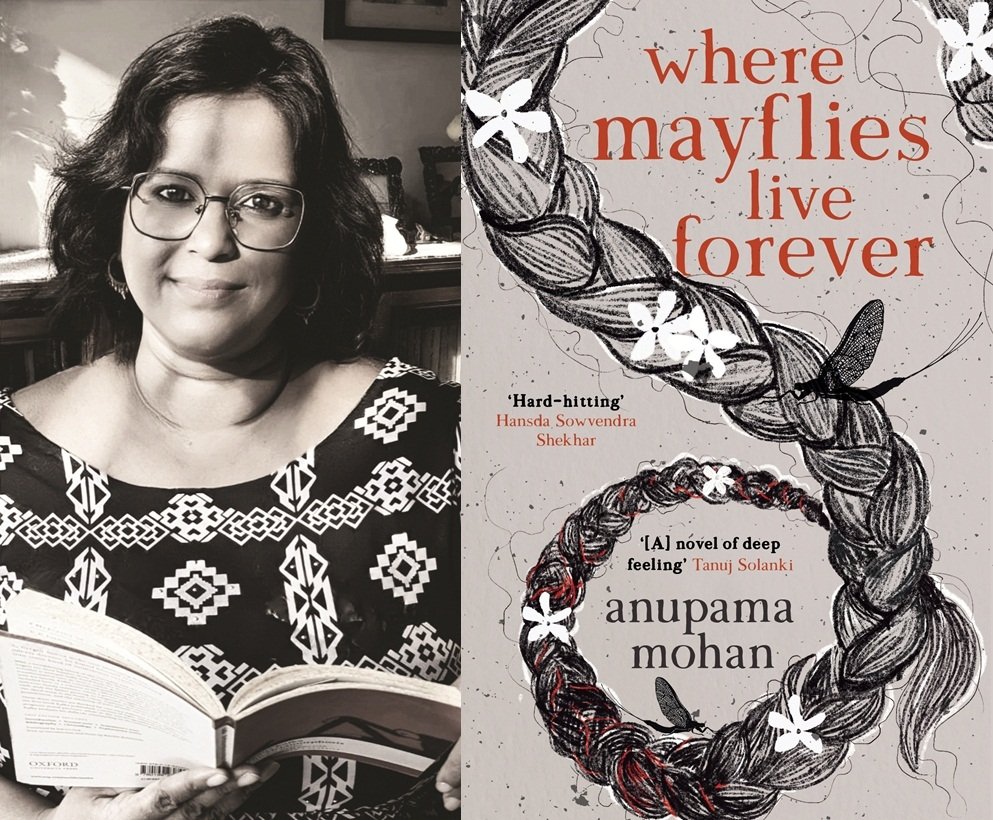

Anupama Mohan Sublime Book Delves Into The Legacy of ‘Tamizh’

NEW DELHI, (IANS) – Growing up in the vibrant surroundings of Central Delhi’s Karol Bagh, Anupama Mohan began writing at the age of nine — “at least, that’s how far back my memory of something tangible — a diary, a journal — goes”.

Not surprisingly, her debut novel “Where Mayflies Live Forever” (Picador) is as much a suspenseful mystery as it is a story about one woman’s self-discovery in the natural world, with a disillusioned but probing, and ultimately triumphant, heart — completed during a residency in Kerala at the height of the pandemic.

Written in fiery yet sublime prose and rendered with extraordinary power, “Mayflies” is an absorbing exploration of violence and trauma, choice and identity, and the journey to find oneself in the wild.

Mohan went to the University of Toronto in Canada for a Ph.D. in English literature. Tracing some of the highlights of her life abroad and her decision to return to India, Mohan said: “In 2010 when I graduated from the PhD program in U of Toronto, the economic recession of 2008 had begun its chokehold on jobs and career opportunities for humanities graduates, in particular.”

“In that year, I was the only one in my cohort to secure a tenure-track position at University of Nevada, Reno, so off I went in 2010 to the deserts of Nevada where the oasis of Reno was to be my first academic home.

“I worked and stayed in Reno for three years when I decided, with my spouse, to return to India to accept a position at the newly resurgent Presidency University (erstwhile Presidency College) in Kolkata. I have lived and worked for the past nine years in Kolkata, having taken to the city and to its incredible culture like a fish to water,” Mohan elaborated.

At the height of Covid, she had the “incredible opportunity” of being selected as the 2021 Writer-in-Residence by Samyukta Research Centre in Thiruvananthapuram. “

About the journey of this book from concept to conclusion and the research that went into it, she said: “Would you believe me if I told you that the plot of the novel came to me in a dream? I got up from sleep one night quite suddenly and woke up my partner and told him the whole story and he, groggy and alarmed, heard me fully before crashing to sleep again.”

“When I started the book, it was titled ‘A Quiet Place’, and at its core was a very simple idea: of a woman rushing out of her home looking for some quiet. The book was always, for me, a philosophical meditation on what it means to be human and what happens when something occurs that completely shatters your sense of your own humanity. Can one recover from such dispossession? If yes, how? And what comes after?

“So, these were the questions I was pursuing. The frame story of a violent act provided a kind of extreme limit at which one is forced to assess the point of one’s existence and come up with an answer,” Mohan said.

Residents of a small town in Tamil Nadu are stunned by the beheading of a prominent man, whose head is missing from the scene of the crime. Everyone suspects Veni, a geography teacher at the local school, but she appears to have vanished from the face of the earth.

As the police gather testimonies from those who closely knew Veni, unsettling truths about this seemingly unknowable woman’s past gradually come to the fore. Where is Veni?

The question haunts her family and other townsfolk, but the investigating officer has a different problem: Who is Veni?

Language plays a key role in the novel.

“The key to the novel,” according to Mohan, “was the construction of a ‘language-world’ for its main cast of characters that will read to the Anglophone reader as a kind of translation of a vernacular (in this case, Tamizh). I was very clear, from the beginning, that their utterances had to be conveyed in English that was shaped by the local language.

And of course, Tamizh is a world language with an unbroken history of nearly 2,500 years. It is a language that is much, much older than English and beats to very different rhythms. The challenge was to write the story in an idiom that would come closest to its characters and their milieu.

“In its everyday avatar too, Tamizh is a very literary language, bursting with colorful idioms, imagistic word pictures, and witty and clever wordplay (as many other Indian languages also tend to be).

“My challenge was to capture these aspects in English but in a way that convinced the reader that these belonged to Tamizh and not to English. Indeed, in the speech style of one of the characters, it is English that becomes vernacularized.”