Perfumes! India Has A Huge PR Problem

By ALKA JOSHI

Special to India-West

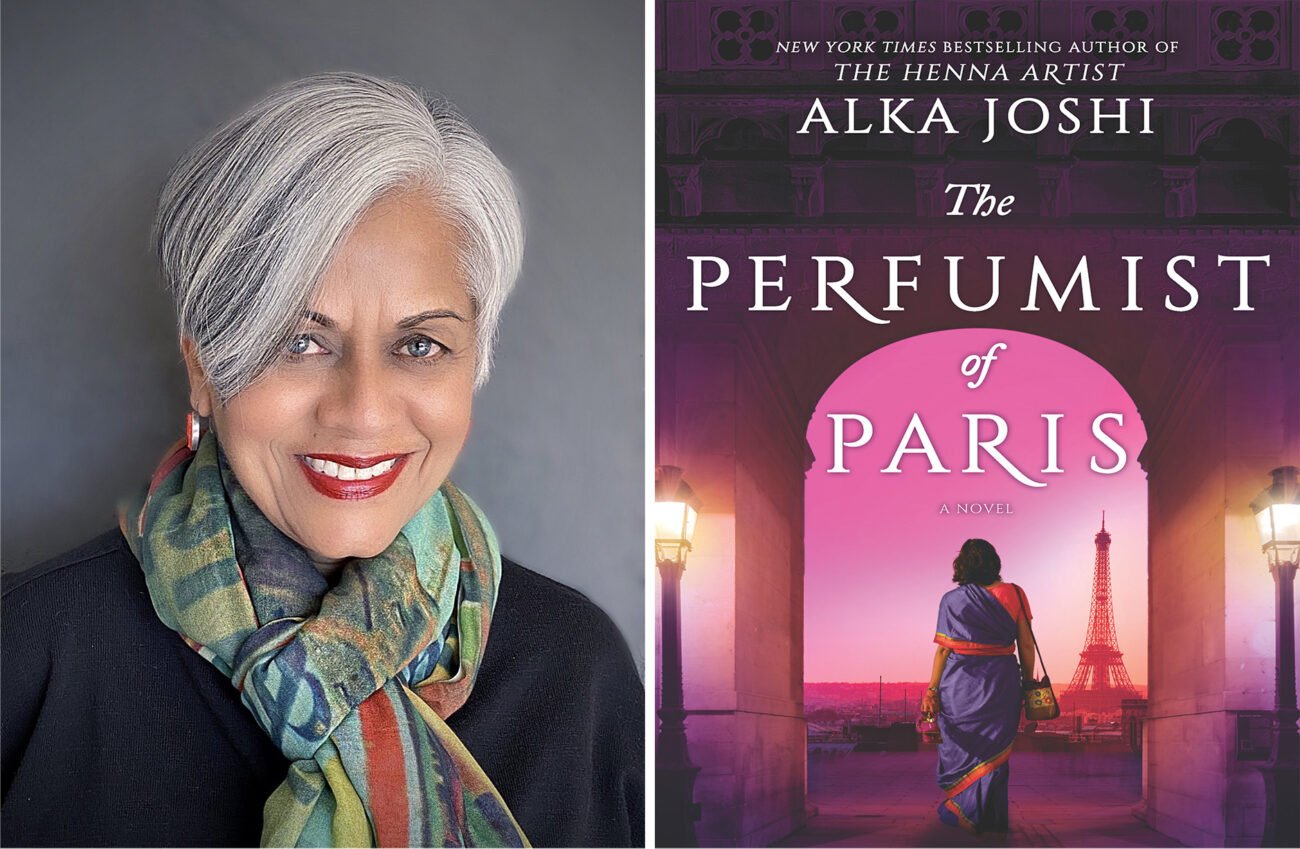

Alka Joshi is the internationally known bestselling author of the Jaipur Trilogy: The Henna Artist, The Secret Keeper of Jaipur , and her latest, The Perfumist of Paris. Her debut novel, The Henna Artist, immediately became a New York Times Bestseller, a Reese Witherspoon Pick, and was LongListed for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. It has been translated into 29 languages and is currently in development at Netflix as a tv series. Joshi was born in India and came to the U.S. with her family at the age of nine. She has a BA from Stanford University and an MFA from California College of Arts. Here in her own words:

When I first started researching perfume for my third novel, The Perfumist of Paris, I had no idea that all roads would lead back to India. Neither did my protagonist, Radha. And that made me wonder: Does India have a PR problem?

My adventure started in New York City, the perfume capital of America, where I met with Ann Gottlieb, the powerful woman behind Dior’s J’Adore and CK Eternity among others. Ann invited me to lunch with master perfumer Carlos Benaim and arranged a tour of the formidable International Flavors and Fragrances (IFF) lab. After observing the lab assistants and, later, interviewing them, I could well imagine Radha in her fictional fragrance lab, pulling vials of sandalwood oil, bergamot, and tuberose from her perfume “organ” to blend a “juice” that her boss/master perfumer had developed.

At IFF, I also met master perfumer Loc Dong, who has collaborated with Ann to create fragrances like Euphoria and Marc Jacobs. Originally from Vietnam, Luc told me his preference for ingredients originated from the scents found in his native country. Mango. Jasmine. Ginger. Those were the same fragrances I had always loved – scents from my native India. Until that moment, I had never stopped to wonder about the origin of the myriad ingredients blended to create perfume.

I dug out a photo taken when I was five years old: I’m sitting with my mother in the garden of our house in Rajasthan. She is elegant in her cerulean sari, red lipstick, and a garland of jasmine flowers threaded through the braided bun in her hair. The jasmine vine grew along the back fence of our house.

And the scent of sandalwood! This soothing essential oil is the base note of many of the world’s most popular fragrances. In Southern India, the slow-growing tree is now protected because of its popularity with perfumers. Its scent is as familiar to me as my mother’s jasmine-scented hair.

I flew to Paris, eager to talk to more perfumers about the inspiration for their favorite ingredients. One of the creators at Firmenich, another fragrance powerhouse, had been raised in Morocco. She referenced the scents of her youth – cloves, bergamot, cinnamon – to design her fragrances.

My next stop was Grasse, followed by Lisbon. In each city, I learned more about the many fragrance ingredients that originally came from India, the Middle East and Northern Africa. Ancient texts confirm the use of ingredients like frankincense, myrrh, and vetiver in ceremonies, palaces, and mosques. Not until the fourteenth century did Europeans begin using scents in daily life—primarily to mask body odor created by poor sanitary habits. At the time, they believed bathing could be harmful so they used strong fragrances to disguise the odor of their own unwashed bodies.

I thought back to my junior high history classes—the stuff of Marco Polo, Alexander the Great, and Queen Isabella. The earliest European traders traveled the renowned spice and silk routes of the East. It was in those hot, tropical regions that traders discovered aromatic ingredients like cloves and cinnamon that their European customers would pay dearly for. Case in point: cloves were once so precious that they were traded for gold.

European demand for fragrances grew quickly. Soon enough, plants like tuberose, orange blossom, and lavender were brought from India and the Mediterranean and planted in southeastern France, in the city of Grasse. The city’s temperate climate made it possible to produce fragrances more cost effectively.

Arabs and Hindus alike had long adorned themselves with intense scents like vanilla, ylang-ylang, and oud long before Europeans discovered them. Why then was I just learning about the olfactory contribution of the East to the West? Why had the fragrance industry not publicly acknowledged this largesse? Why, instead, was France reputed to be the perfume capital of the world when the title rightly belonged to countries further East and South?

The more fragrance information I uncovered, the clearer it became to me that the world’s finest fragrances owed their success to what they originally harvested—and still procure—from countries like India, the nation of my birth. Which begged the question: why has India not done more to counteract its oft-displayed reputation as a poverty-stricken, underdeveloped country by promoting the story of the origin of fragrances?

I didn’t start out with that goal, but that’s precisely what I ended up doing in The Perfumist of Paris. My protagonist took me there. Working for a tony perfume company in 1974 Paris, 32-year-old Radha travels to India in search of the missing ingredient for her fragrance project. And she finds it in the moist and sugary soil that India’s monsoons leave behind. The scent is mitti ittir.

If I can write well-researched novels that promote India’s gifts to the world, why isn’t the Indian government promoting her delights as well? Delights like intricate henna designs, thousands of herbal remedies that have inspired the West’s “golden lattes” and “chai teas” and…enticing scents that perfume our bodies, our homes, and our environments.

Think what this could do for India’s reputation in the world. A slight incline of the head: I’m listening. A raising of the eyebrows: well, that’s a surprise! A perceptible gasp: all this time? Such a revelation would create an adjustment of expectations for the better.

I would apply for a PR position at India, Inc., but I’m a little busy writing novels.