In South Asians, Belly Fat Is A Key Indicator Of Cardiovascular Health

By Dr. Ravi Dave

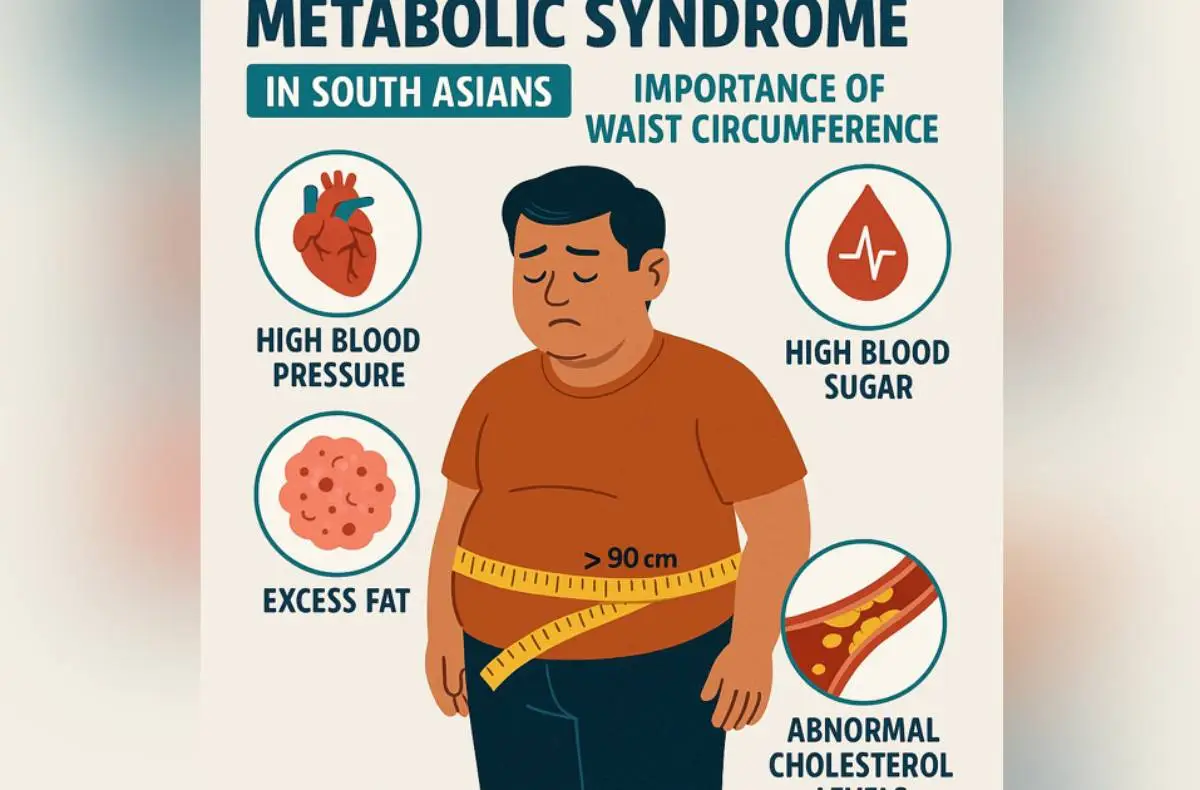

South Asians have a four-times greater risk of heart disease compared to the general population. While traditional risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol are well-documented, groundbreaking research is uncovering additional risks—specifically those tied to fat accumulation around the belly.

Obesity, defined as abnormal fat accumulation, comes in two types: peripheral obesity, where fat is stored under the skin across the body, and central obesity, where fat accumulates around the belly, liver, and internal organs.

In routine physical exams, doctors typically measure height and weight to calculate Body Mass Index (BMI) as an estimate of body fat percentage. A BMI over 25 indicates overweight, and over 30 indicates obesity—both associated with increased medical risks. However, BMI is primarily effective at assessing peripheral obesity and does not accurately reflect central obesity, which poses a particular challenge when evaluating South Asian patients.

Due to genetics and other factors, South Asians often have a unique body composition. Even at lower BMIs, many South Asians carry more visceral (belly) fat compared to others. A commonly recognized stereotype—the combination of thin limbs and a prominent belly—reflects this reality.

Central obesity, often overlooked by BMI, has a significant impact on our internal health. After a meal, nutrients such as sugar enter the bloodstream. The hormone insulin removes sugar from the blood and delivers it to cells for energy. However, belly fat is metabolically active and releases chemicals that make insulin less effective. As a result, blood sugar remains elevated, prompting the body to produce even more insulin. This cycle not only increases hunger and weight gain but also leads to metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions including elevated triglycerides, low HDL (“good”) cholesterol, high blood pressure, and high fasting blood sugar—precursors to diabetes and heart disease.

Fortunately, simple steps can help us assess and manage these risks. Measuring waist circumference at the level of the belly button provides a quick and effective assessment of central obesity.

A waist measurement greater than 35 inches for men and 31.5 inches for women is considered abnormal. Given that many South Asians develop diabetes and heart disease at younger ages and lower body weights, waist circumference is a critical screening tool for early detection and prevention.

In addition to screening, lifestyle changes—such as adopting a healthier diet, engaging in regular physical activity, and managing stress—are essential to protecting cardiovascular health.

I encourage my fellow South Asians to be proactive: eat thoughtfully, move purposefully, and support one another. These small yet powerful steps can greatly enhance our collective health, prosperity, and future.

(Dave is a professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the Director of the UCLA South Asian Heart Programsupported by the Jivrajka Family Foundation. UCLA Health South Asian Heart Program.)